Share This

What do you think of when you think of Chinese food? White rice and Peking duck? White noodles fried in MSG? White dumplings stuffed with greasy ground pork? White steamed buns filled with nothing at all? If that’s all that comes to mind, you’re only thinking of the American interpretation of one of the world’s most varied and longest-lasting cuisines. Sadly, you probably won’t be alone in your assumptions – most of us have never had authentic Chinese cuisine that hasn’t been tweaked for the American palate. Don’t get me wrong, the Chinese love their savory fatty salty dishes, but if you can’t imagine beyond the refined grain white-out, you’re missing some of the most interesting dishes of all.

Having spent two full weeks in Beijing in April, I’m pleased to say whole grains are absolutely part of traditional food culture in Beijing. Yes, refined grains tend to dominate their food scene – decades of food insecurity and “whole grains = hardship” have left modern Chinese people with the perception that whiter is better. This isn’t very different from the dominant view most Americans had just ten short years ago, wrinkling our collective noses at “that whole grain hippie food” while reaching for our refined bread, rice, and pasta. Whole grains remained in certain niche food categories, taking center stage only rarely in our granolas, heavy dark breads, or instant oatmeal breakfasts. What sets our past apart from China’s present is several thousand years of embracing food as medicine, a long-standing tradition that is alive and well in the hutongs of Beijing.

For those not in the know, hutongs are narrow streets or alleys that stretch between main roads and boulevards throughout the center of Beijing. Traditionally, each hutong connects a line of courtyard residences to a main thoroughfare, similar to the way capillaries connect most of the body’s tissue to veins and arteries. And like these circulatory vessels, hutongs are quite literally the lifeblood of traditional Beijing neighborhoods. Homes, restaurants, pharmacies, snack vendors, and stalls selling produce, grains, oils, and other necessities line the hutongs from one end to the other. Some are wide enough for two cars to pass, some only suited for foot or bicycle traffic, and some hutongs are so narrow in places that adults have difficulty squeezing between the walls. Much hutong culture has been lost as modern developers purchase long stretches of land in order to build high-rise apartments, shopping malls, and office buildings. Happily, the hutongs that do remain are full of the sounds, smells, sights, and tastes that define the city’s complex palate.

Enough musings – let’s talk about the food I found!

First up, a corner vendor whose equipment could have been lifted from a food stall in Paris. I recognized the flat, circular griddle as the perfect crepe-making surface, but I’d never heard of crepes being a part of Chinese food culture. Turns out, they aren’t – but super-thin pancakes stuffed with sautéed carrots, bean sprouts, egg, chili sauce, and crunchy bits of double-fried dough strips are. Our guide explained the choices of batter, and lo and behold, two of the three options were purple rice and millet. Throughout the rest of my trip, I noted people carrying these savory breakfast pancakes with them to work in the morning, and sometimes, you could even find people eating them on the streets at night. Street food is a huge part of Beijing culture, the need for on-the-go options echoing the increasingly busy pace of modern city life. And, whether eaten as breakfast or dinner, the whole grain pancakes I enjoyed were definitely satisfying options for a fast and tasty meal.

Further along our wanders, we stopped at one of the many little local stores supplying goods to hutong residents. Massive sacks of grains and beans covered the floor and various types of oils in bottles of all sizes lined the walls. The shop also sold large bags of fresh eggs and dried cat food by the scoopful, but what captured my focus were the sacks themselves. Red and white beans rubbed proverbial elbows with millet, black rice, cornmeal, and seeds. We learned that most hutongs have little shops like this, where grains and oils are sold together, but produce and meat never cross the threshold. It reminded me of the souks of Marrakech, where every stall and vendor had a particular specialty, and the tin lamp artists never sold leather goods.

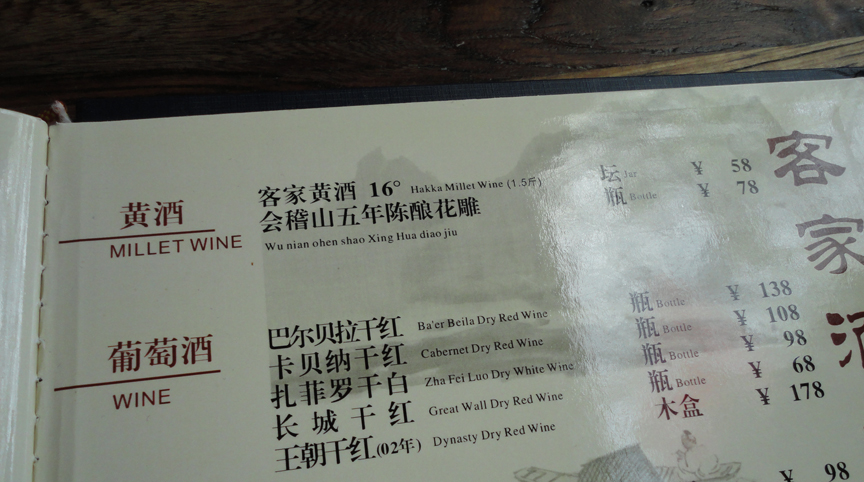

For lunch, we stopped at a food court unlike any I’ve ever seen in the states. Set in the top floor of an indoor bazaar, hungry customers could wander from one seller to the other, checking out the various specialties. One vendor sold fruit juices, another beer and soda (bing pijiu!), while still others sold steamed buns or noodles or stir-fried veggies. All the tables were in the center of the floor, and the process of actually eating was simple – pick your food, then take a seat while everything is cooked for you and brought to your table. We nibbled on hot and sour chicken, cold sauced carrots and sprouted soy beans, steamed broccoli, and buckwheat noodles tossed in a tangy stir-fry sauce. I was so excited to see the buckwheat noodles that I didn’t even care what they’d been cooked in; it could’ve been horrid and I would’ve eaten till I burst just on general principle. Lucky for me, everything was fantastic! I just wished we’d found the menus on our way in instead of on the way out – I totally would’ve ordered the millet wine!

The last hutong stop was the cutest little snack stall run by the cutest little Chinese man I’ve ever seen. His eyes positively lit up when he spied our guide, and quickly began portioning out a few pieces of this, a chunk or two of that, all the while chattering with our guide in the universal tone of a neighborhood gossip. In-between the veggie dumplings and little pieces of glazed chicken, I spied a tray of buns that looked almost exactly like English muffins. I asked our guide about them and was totally floored to learn they were a traditional Chinese Muslim pastry made from “dark wheat flour.” After a bit of debate, it finally became clear that these little biscuits are indeed made from whole wheat flour and a savory mix of spices including caraway seeds. Salty and tangy, flaky but hearty, the shopkeeper explained through our guide that they’re used in one of the most popular breakfast items he makes – an egg and veggie sandwich.

It’s unlikely that the hutongs will ever vanish completely, but they may indeed become an endangered species in the years to come. The plight of the hutongs is oddly parallel to China’s struggle with highly refined and processed foods – how does a culture make room for modern progress without losing sight of their heritage? How can the Chinese people build for the future upon their long history of healthy food in a way that helps put aside the hardships and misconceptions of more recent generations? It may be that the answers lie somewhere within the twisting, bending pathways of Beijing hutongs, tucked within a snack vendor’s stall or between one courtyard and the next. If so, they’ll be found wrapped inside a millet or purple rice pancake, sold beside buckwheat noodles, and sandwiched within a salty whole wheat biscuit. (Kara)

Add a Comment