Share This

In 1519, when Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Aztec empire’s capital city of Tenochtitlan, amaranth – sometimes called the “food of immortality” – was the second most important food crop in the Americas after maize. However, the Spanish invaders quickly began to restrict production of the crop in order to defeat the Aztec people and suppress their culture and traditions, and amaranth’s role supporting an empire of 5 million people began to wane. Now, many centuries later, the popularity of amaranth is on the rise again as consumer interest in ancient grains grows and farmers facing the challenges of climate change have begun seeking crops that are more resilient and adaptable.

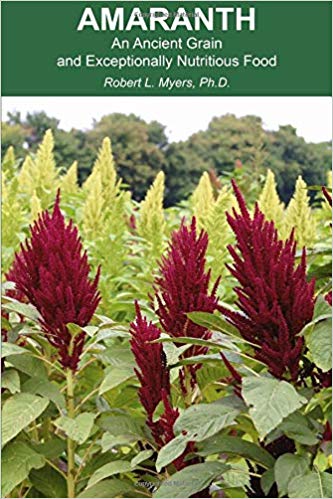

Our 2018 Consumer Insights Survey found that today, one in six US consumers (16%) are familiar with amaranth by name, but only 5% report having actually tasted it, which seems a little surprising when you consider that its distant cousin, quinoa, has become such a grain sensation over the past decade. We recently caught up with Dr. Rob Myers, a plant scientist at the University of Missouri and author of the book, Amaranth: An Ancient Grain and Exceptionally Nutritious Food, to learn more about this visually striking crop and its role in our food system. Rob has been growing amaranth for almost 30 years and is one of the foremost authorities on this crop in the US.

From an agricultural perspective, amaranth has several huge advantages over other major crops, but perhaps the biggest benefit is its drought tolerance and extremely low water requirements. In fact, Rob tells us that “irrigation is seldom needed unless growing in the most moisture-deficient areas.” Unlike crops like corn, whose leaves curl up and brown under moisture stress, the response mechanism in amaranth plants is to “droop or wilt so that they stop transpiring water,” explains Rob. “The viability of those amaranth leaves is maintained and they can quickly recover once some moisture is restored.” Amaranth’s tolerance to hot, dry weather is a highly desirable trait in many farming regions, and the fact that it’s adapted to a wide range of growing conditions, and does well in a variety of elevations means that it’s relatively easy for farmers across a wide range of geographies to add it to their rotation.

In the 1990s Rob knew roughly 100 farmers in the US who were growing amaranth, but no one was growing quinoa. Back then, he told us, if someone had asked him which crop—amaranth or quinoa—would be playing a huge role in our food supply today, quinoa would not have been his guess. His theory about why quinoa’s popularity has far outpaced amaranth’s despite being much more difficult to grow outside its native Andean region in Peru and Bolivia, surprised us. While flavor and texture may have played a role, Rob believes quinoa’s lighter color is simply more appealing. He explained that humans have always tended to select for lighter-colored grains and there are many examples of crops (such as soybeans) whose wild relatives are much darker than the varieties we cultivate. It’s possible that this preference for paler seeds exists because it has allowed us (and our ancestors) to more readily spot dirt, bad seeds, and other impurities in our grain supply.

Darker color aside, amaranth’s nutritional profile is just as impressive as quinoa’s. Like both quinoa and buckwheat, amaranth is considered a “pseudocereal,” because even though it’s not in the same botanical family as cereal grains (such as corn, wheat, rice, etc.), it’s used culinarily just like any other grain and its nutritional profile closely resembles that of a cereal grain. Unlike cereal grains, however, all three of these pseudocereals are considered “complete proteins,” which means that they contain a good balance of all nine essential amino acids required by the human body, whereas most cereal grains are limiting in at least one.

Amaranth’s use in food products these days is quite varied, and we see it showing up in its intact form, as a flour, and even as a puffed or popped component of cereals and granola bars. Rob believes that the wide range of potential product applications is very promising and that the primary limitation to amaranth’s more widespread adoption may be the absence of a “coordinated system between growers and buyers.” There has been a recent resurgence in the development of regional grain systems that connect growers and buyers more directly and we hope that as interest in sustainable ingredients and ancient grains continues to grow, we’ll see more of these connections being made.

Interested in trying amaranth yourself? Rob’s book has lots of tips for growing it in your own garden and we’ve got recipe ideas waiting for your first harvest! (Caroline)

Comments

Add a Comment