In an age of “Facebook Science” and rumors, many myths about grains are widespread. Whether you’re a journalist writing for the press or a concerned individual using your own social media channels, we hope you’ll use the information on this page to get to the facts about some common myths on grains. Contact Kelly if you have a question about any other grain controversies.

MYTH: Whole Grains Cause Inflammation

Whole grains are part of the solution, not the problem, when it comes to inflammation. That’s important, because research increasingly shows that systemic inflammation may fuel many diseases, from allergies to heart disease to cancer. In a recent clinical trial, researchers at the University of Nebraska showed that eating a cup of whole grain barley or brown rice (or a combination of the two) for as little as four weeks can increase the “good” bacteria in your gut that fight inflammation. (Read our blog on this study.) In another randomized controlled trial, this time in Iran, overweight girls were divided into two groups, one eating mostly refined grains and one eating mostly whole grains. There was a significant reduction in inflammation markers among those eating whole grains.

MYTH: All Grains Make Your Blood Sugar Spike

Research links many chronic diseases, from diabetes to heart disease, with diets that send your blood sugar on a roller coaster ride. Indeed, when you eat certain foods, especially those high in refined, highly processed grains and sugar, your blood sugar can spike – then quickly plummet, leaving your energy depleted and causing damage to some bodily systems. It’s healthier to choose foods that provide a steady, slow release of glucose (blood sugar).

The Glycemic Index rates how quickly carbohydrate foods are converted into glucose – and you may be surprised to learn that many grain foods have a low GI score (55 or less on the 1 to 100 GI scale is considered low). Virtually all intact whole grains have a very low GI score: whole grain barley has a GI of about 25, wheatberries about 30, rye berries about 35, buckwheat about 45, and brown rice about 48, to cite a few examples.

The big surprise? Pasta has a low GI score, with whole grain spaghetti rating about 37, and even “white” pasta coming in at 42-45. That’s because the starch structure of pasta causes it to be digested much more slowly than the same amount of flour made into bread. So look for intact whole grains and pasta to enjoy grains that will fuel you slowly and steadily.

MYTH: U.S. wheat is genetically modified

The book Wheat Belly (and many other sources) attest that wheat in the U.S. food supply has been genetically modified. In fact, there has been no GMO wheat commercially available – in large part because U.S. farmers have fought hard against GMO wheat, out of concern that it would put a damper on the export market for U.S.-grown wheat. However, one variety of GMO wheat was approved by the USDA in 2024, and may eventually enter the food supply in the future.

MYTH: Wheat is the reason we’re overweight and obese

While eating too much of anything can make you fat, wheat plays no special role in putting on the pounds. Wheat makes an easy scapegoat, but other countries with much higher per-capita wheat consumption have much lower rates of overweight and obesity. (The French, for instance, consume nearly twice as much wheat per person as Americans, but have about one-third our obesity rate.)

Weight problems are almost never the fault of one food; it’s total diet and lifestyle that matter. Go ahead and enjoy your whole grains, especially in their intact and traditional minimally processed forms, in the context of a diet overflowing with fruits, vegetables, legumes, fish, olive oil, and other health foods. If you eat a healthy diet comprised of whole, minimally-processed foods in reasonable portion sizes, you do not need to fear succombing to “wheat belly.” A whole grain cookie (even a gluten-free one) is still a cookie.

Peer-reviewed scientific journals have rebutted the misconceptions in pop-science books like Wheat Belly. Here are two good articles that take a point-by-point approach:

“Wheat Belly – an Analysis of Selected Statements and Basic Theses from the Book” Julie Jones, Cereal Foods World. July-August 2013, 57(4):177-189.

“Does Wheat Make Us Fat and Sick?” Brouns et al., Journal of Cereal Science. 58(2013) 209-15.

In January 2018, Prof. Fred Brouns published an article that takes a scientific approach to separating truth from fiction when it comes to myths about wheat and gluten. You can find his article here.

MYTH: Modern dwarf wheat has been bred to contain more gluten

Donald Kasarda, PhD, a scientist with USDA’s Agricultural Research Service, investigated this allegation in a paper that appeared in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry in early 2013. He surveyed data from the 20th and 21st centuries and concluded that gluten content in wheat has not in fact increased.

In a speech at the International Celiac Disease Symposiumi in Chicago in September, 2013, Dr. Kasarda also stated that dwarf wheat is a natural cultivar and that the genes for dwarfism and for gluten are not associated in the genetic makeup of modern wheat.

Two caveats here. Kasarda’s data do show that average consumption of gluten is rising, especially in the last 15-20 years. That’s because gluten is being added as an isolated ingredient in so many processed foods. (Not an issue, if you eat your foods more on the intact / minimally processed end of the scale.) Research also shows that wheat has been bred to increase its pest resistance — a worthy goal to save the environment through use of fewer pesticides. Some people are sensitive to these compounds (ATIs, or amylase tripsin inhibitors), however.

MYTH: We’re simply eating more wheat than ever

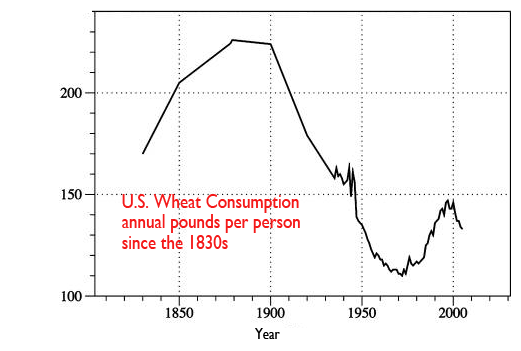

Another argument says that wheat is doing us in because we’re suddenly eating so much more than we ever have. Not so. US wheat consumption hit a peak in the 1870s of almost 230 pounds per person per year. It then dropped steadily until the early 1970s, when it rose once again, as fast food restaurants and supermarkets made more different wheat-based foods more readily available. In the last decade, wheat has once again dipped – and is now at about half its peak.

That said, we recommend you change out some of the wheat in your life for other grains. When our doctor says “eat more vegetables” we don’t simply eat carrots and leave it at that, as healthy as carrots are. No, we understand instinctively that it’s important to eat a variety of vegetables to get a range of nutrients, textures and tastes. Same thing goes for grains, folks. Wheat’s just fine, but change it up!

MYTH: Our wheat is toxic because it is “drenched in glyphosates” before harvesting

Monsanto’s Roundup is the best known of a group of herbicides referred to as glyphosates. A very small percent of the US wheat crop – estimated by Dr. Jochum Wiersma, an agronomist at the University of Minnesota, at less than 2% of the total crop – may be sprayed with glyphosates about a week before harvest. This is done for two reasons: to eliminate weeds that may otherwise impede harvesting, and to help the wheat dry more quickly and evenly. This practice is uncommon and is limited to areas with a short growing season, when weather has been unusually wet.

Dr. Brett Carver, Regents Professor at Oklahoma State University, told the WGC, “Glyphosate represents an extra expense that farmers will not accept unless there is absolutely no other way to get the crop out… In most US wheat regions, it takes a situation of no-other-choice desperation to consider glyphosate as a harvest aid.” In Carver’s opinion, the practice would be a pointless waste of money in dryer areas like the southern and central Plains. Wiersma says the same would be true of the Pacific Northwest; only areas such as the Dakotas and Minnesota are likely to turn to this alternative, and even then not routinely.

Dr. Wiersma points out that in any event, herbicides applied so soon before harvest are not taken up internally into the wheat kernels (because the plant has already matured); externally, the “glumes” (inedible outer layers) protect the edible wheat kernel. We would welcome anyone who would analyze such wheat and prove the lack of uptake, however, especially since the WHO has determined that glyphosate may contribute to cancer. (The WGC notes: Anyone concerned about this practice could consume organic wheat, rather than forego wheat.)

MYTH: Eliminating wheat cures diabetes / abnormal glucose tolerance

No, eliminating wheat will not cure diabetes or abnormal glucose tolerance. In fact, evidence continually shows that a high intake of whole grains (including whole wheat) reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes as much as 21-30%. Overeating any type of food can cause weight gain and blood glucose abnormalities, whether or not wheat is a part of your diet. The best outcomes come from following nutrition recommendations from physicians and dietitians.

Researchers conducting a 2013 meta-analysis of 16 studies exploring the association between whole grain intake and type 2 diabetes concluded that “a high whole grain intake, but not refined grains, is associated with reduced type 2 diabetes risk.” They suggest the consumption of at least two servings daily of whole grains to reduce type 2 diabetes risk. More recent research suggests a relationship between whole grain intake and insulin action.

In a study in Italy, 53 adults (40-65 years old) with metabolic syndrome followed one of two different 12-week diets. One group consumed their standard diet, but replaced all grains with whole grains, and one group consumed their standard diet, but choose only refined cereals. Researchers found that the whole grain group had significantly lower levels of post-meal insulin (29%) and triglyceride levels (43%) than before the 12-week test period, thus reducing the risk for heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Based on these findings, the researchers suggest that “the whole-grain diet was able to improve insulin action” after meals, thus providing clues about how whole grain diets reduce the risk of chronic disease.

MYTH: Wheat is addictive

Extreme dieters preach avoiding wheat for its “addictive” properties. As ammunition, they say that wheat proteins, called gliadins, can stimulate opioid receptors, thus paving the way for addiction. However, these peptides are also found in milk, rice, and even spinach. And spinach addiction certainly isn’t a problem! Additionally, these studies investigating foods’ opioid potential were done in vitro or by feeding preformed peptides, not actual food.

In a recent study in the Journal of Cereal Science, Fred Brouns confirms that “there are no studies in which gliadorphin has been shown to be absorbed in intact form by the intestine and no evidence that gliadin either stimulates appetite or induces addiction-like withdrawal effects.” Additionally, some studies have actually found these peptides to be beneficial to health, with the potential to improve both blood pressure and learning performance.

MYTH: Everything will be great if we just stop eating all grains

Grains are the most important source of food worldwide, providing nearly 50% of the calories eaten, and are some of the least intensive foods to produce. Suddenly replacing grains with other foods (such as meat) is a shift the earth is not ready for.

As scientists assess the risks and benefits of different food production systems, it is easy to see why grains have been at the core of traditional diets for millennia. Fruits and vegetables, while very nutritious, aren’t as energy dense as grains and are harder to grow, transport, and store for year-round enjoyment. So to make up the necessary calories in fruits and vegetables, much more food would have to be grown. Similarly, raising animals for meat production requires a substantial amount of land and water. For example, beef production uses 10.19 liters of water to produce 1 calorie of food, compared to only 2.09 liters per calorie of fruits, 1.34 liters per calorie of vegetables, and 0.51 liters per calorie of grains. Shifting diets away from grains and towards more energy intensive foods puts an irresponsible burden on our planet’s precious resources.

MYTH: White bread is just as healthy as whole grain bread

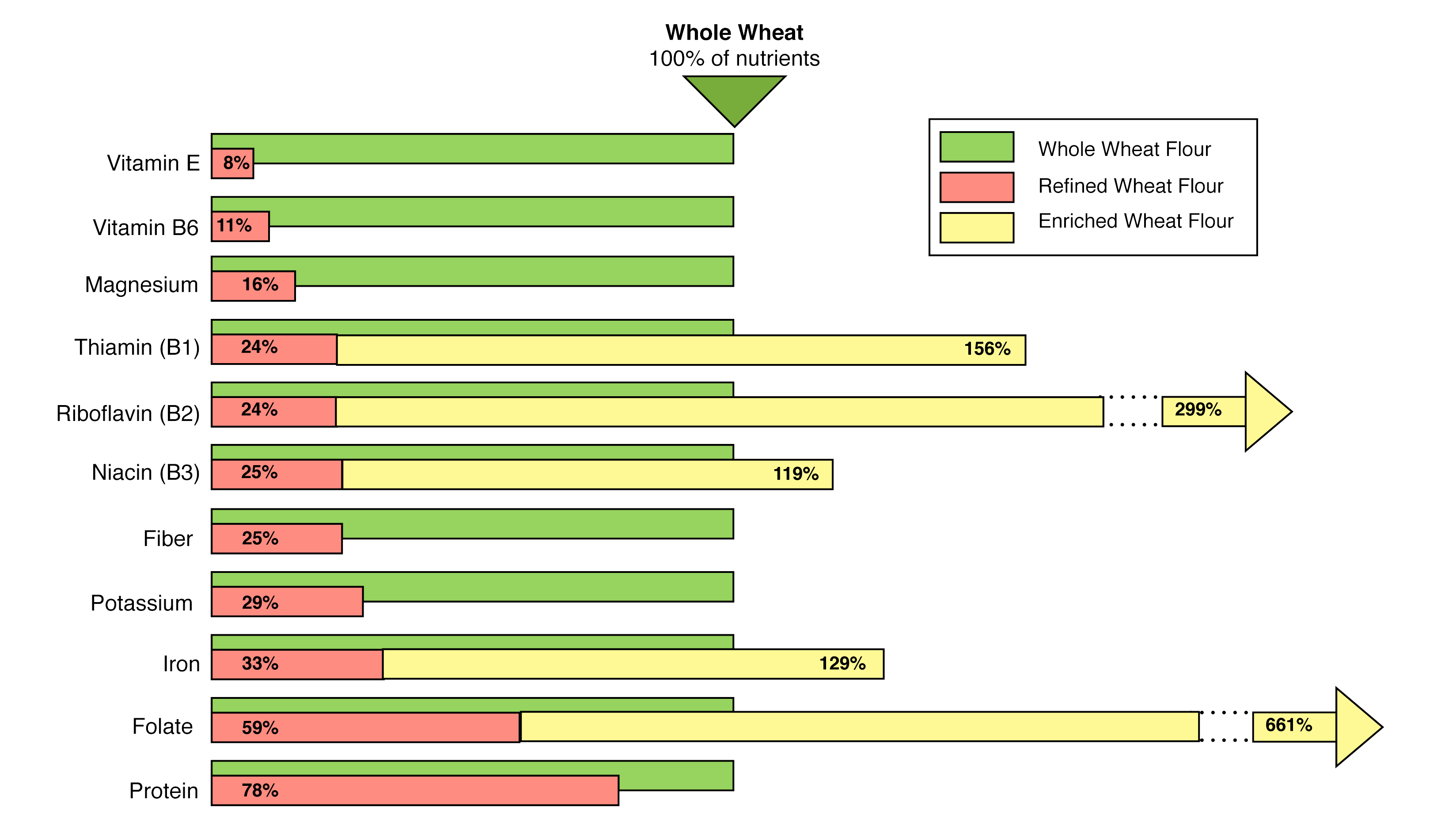

“There IS a measurable difference between whole wheat and white flour products, in every category one wishes to consider,” explains WGC Scientific Advisor Dr. Gary Fulcher. Refining whole wheat flour to make white flour greatly decreases a wide range of nutrients, including fiber, protein, vitamin E, vitamin B6, potassium and magnesium. Below is a closer look at how whole wheat flour differs from refined or enriched wheat flour.

Rabble-rousing headlines claiming that studies find “no differences” between whole grain breads and white breads have been widely critiqued in the academic community, and are at sharp odds with the consensus of scientific research. Breads do tend to have a higher Glycemic Index (GI) than intact whole grains, but, whole grain breads (GI of 69), on average, typically have a more gentle impact on your blood sugar than white breads (GI of 75). Plus, of course, the whole grain breads include all those extra nutrients.

Studies continuously support the health benefits of choosing whole grain foods over refined grain foods. For example, scientists in California found that people burned 50 percent more calories digesting a sandwich on whole grain bread with real cheese compared to a sandwich on white bread with a processed cheese product, even though both sandwiches had the same amount of calories and the same ratio of bread to cheese. Similarly, in a randomized clinical trial of 81 adults, the group eating whole grains had significantly higher concentrations of “good” gut microbes and significantly improved their metabolisms over the six-week study, compared with the group eating refined grains (keeping all other foods the same between the two groups).

Observational studies point to similar findings, linking higher whole grain consumption with a lower risk of being overweight or obese. And where are people getting those whole grains? US national survey data find that whole grain breads are the biggest source of whole grains for children and adults alike.

For more insight on the health differences between whole grain and white bread, see our May 2017 blog on US News & World Report.