Share This

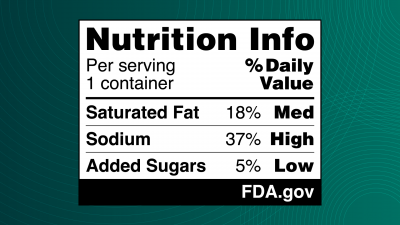

Front-of-pack labeling (FOPL) is one of the most visible nutrition policy tools and has become increasingly popular globally over the last two decades. In the US, FDA has put forth a proposal to make front-of-pack labeling mandatory on food packages, though they have not yet published a final rule. FDA explains that the new label, called the Nutrition Info box, would complement the Nutrition Facts already required on packages:

“Displaying simplified, at-a-glance, nutrition information that details and interprets the saturated fat, sodium, and added sugar content of a food as “Low,” “Med,” or “High” on the front of food packages would provide consumers with an accessible description of the numerical information found in the Nutrition Facts label. Current federal dietary recommendations advise U.S. consumers to limit these three nutrients to achieve a nutrient-dense diet within calorie limits.”

Policy makers around the world have developed a variety of systems and symbols to highlight at a glance some of the key nutritional attributes of a product to help consumers make healthier decisions when shopping. These systems tend to fall into two main categories: (1) warning labels that highlight nutrients to limit like added sugar or saturated fat (much like the proposed FDA label would do), and (2) algorithm-based schemes that provide a composite score or rating using both positive and negative nutritional criteria.

While we wait to hear more from FDA, we thought it might be helpful to dive into the pros and cons of these types of labeling systems and look at how they impact consumer understanding of whole grain products.

Category One: Warning Labels, A Missed Opportunity for Positive Health Messaging

Mandatory warning labels are increasingly common, particularly in Latin America (and likely soon, the US as well). These systems flag nutrients that should be limited, helping consumers quickly identify products high in sugar, salt, saturated fat, and overall calories. While useful in making it easy for consumers to compare products and make quick decisions, these labels tend to oversimplify food choices, providing consumers with only one side of the story. By focusing solely on what to avoid, they fail to recognize the positive attributes of foods—such as whole grain content—that are essential for a balanced diet. As the 2019 Global Burden of Diseases Study and related research makes clear, the health risks associated with not consuming enough whole grain actually outweigh the risks of consuming too much salt, trans-fat, and sugar. The fact is that increasing healthful ingredients is just as important, if not more so, than decreasing detrimental ingredients.

In fact, research shows that consumers respond more favorably to nutrition messages that are framed in a positive way, rather than messaging that focuses on what consumers shouldn’t do and shouldn’t eat. It is just as important for consumers to understand the beneficial contributions that a product will make to their overall diet as it is to warn of them of the more negative nutritional attributes of that product. Most foods are not just “good” or “bad” and they often have a mix of both beneficial and detrimental ingredients. Changes in dietary patterns and habits are almost always incremental, and foods that have both positive and negative nutritional characteristics can be great “bridge foods” as people move along their journey to better health.

Category Two: Algorithm-Based Labels, A More Holistic Approach with Room for Improvement

Many of the voluntary labeling schemes used around the world fall into this second category of policies which utilize algorithms to provide a more holistic view of a food’s healthfulness. Some examples of these systems include the Nutri-Score used in Europe and the Health Star Rating used in Australia and New Zealand. While many of these systems account for fiber content, most of them exclude any direct measure of whole grain content from their algorithms. This omission can disadvantage whole grain products.

Research shows that using a measure of whole grain content in nutrient profiling systems, rather than fiber alone, better aligns front-of-pack labels with dietary guidance. In fact, the inclusion of whole grains in labeling schemes has greater potential to improve overall diet quality for those using the FOPL guidance. Research on the Health Star Rating system has shown that it “fails to effectively distinguish between refined and whole-grain items and hence [fails to] communicate the benefits of consuming mainly whole grains.” However, modeling the addition of whole grains to the nutrient profiling system made the distinction between whole and refined foods much clearer, promoting whole grain products over their refined grain counterparts.

The Gold Standard: Harnessing the Potential of Whole Grains in Nutrient Profiling Systems

In contrast to systems that use fiber as a stand-in for whole grain content, the Nordic Keyhole labeling system—used in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Iceland, Lithuania, and North Macedonia—offers a more progressive model. Since 2009, it has incorporated whole grain content into its algorithm. A 2015 Swedish Food Agency study found that consumers who selected foods bearing the Keyhole symbol increased their whole grain consumption by 754%, compared to a 30% increase in fiber intake. While fiber is one of the many beneficial components of whole grain foods, these foods offer more than fiber alone, and different whole grain ingredients vary in their specific fiber content. It is more meaningful to use a measure of whole grain content itself than it is to approximate whole grain content via fiber as proxy.

As more countries develop FOPL systems, including the US, there’s an opportunity to better align nutrition labeling with dietary recommendations and make these labels a powerful consumer tool for health. We’re eager to see where the conversation in the US lands and how well the resulting system works, especially when it comes to helping consumers find and choose whole grain foods. (Caroline)

To have our Oldways Whole Grains Council blog posts (and more whole grain bonus content!) delivered to your inbox, sign up for our monthly email newsletter, called Just Ask for Whole Grains.

Comments

Add a Comment