Share This

No longer breaking news, sourdough baking has been on the rise for months now, and hopefully is here to stay! And who can blame these new, home-baking, sourdough enthusiasts? The joy of pulling a freshly-baked loaf out of the oven creates a feeling of accomplishment hard to rival, not to mention how amazing fresh bread tastes. In addition, because sourdough is naturally fermented, it is easier on the digestive system. At the WGC, we’ve been celebrating the sourdough trend via blog posts and webinars, and we’re chiming in once again to remind you that the world of sourdough isn’t just limited to the fresh, crunchy European-style loaves we are used to seeing on social media and baking blogs. Sourdough is global, and offers a glimpse into rich culinary histories.

Bread has been a staple of global human nutrition for thousands of years, even before the advent of agriculture. Early bread was all unleavened because humans had not yet discovered how to use fermentation to make bread rise. This unleavened bread, sometimes known as flatbread, was made by mixing a simple dough of roughly-ground grain and water and baking the resulting dough on hot stones or in ashes.

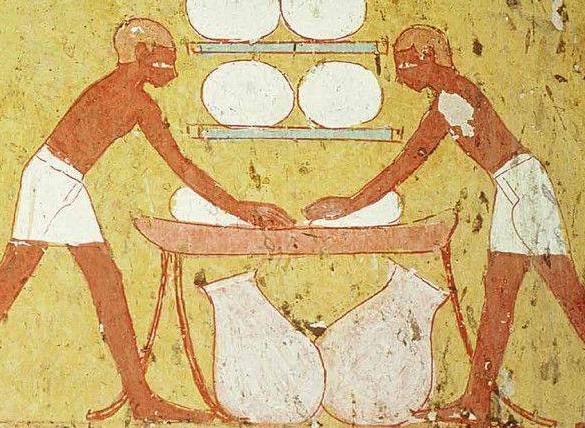

The first recorded example of leavened bread, indicating the use of fermentation to make bread rise, was created by the Ancient Egyptians. They even put fermentation to further use by leveraging their knowledge to process beer! While it is impossible to know origin story of leavened bread, it is easy to imagine a simple dough being left out too long, producing a strange, sour smell and small bubbles. Perhaps alarmed by this progression, or curious, the mixture is thrown into a fire. And the rest is history!

A brief look into traditional fermented breads offers bakers a chance to try some new treats with exciting flavor profiles, often imparted by the use of grains other than wheat. Below we share 5 examples of traditional fermented breads, highlighting different grains.

Rugbrød

Rye has a long and important history in Scandinavia. Rugbrød is one of the oldest Danish breads, traditionally made with rye. This dense loaf usually takes the shape of a long rectangle, no more than 12 cm high. Though many breads transitioned to the use of commercial yeast by the early 20th century, Rugbrød relies on natural fermentation for its signature tangy flavor so has maintained its naturally-leavened status. Remember, don’t expect this bread to rise like wheat bread – if at all. Rye has different proteins than wheat, and doesn’t create the same cohesive gluten bonds, keeping this loaf deliciously tight, crumbed, and dense.

Kisra

Kisra is a thin fermented bread made in what is now Chad, Sudan, and South Sudan. Its thin pancake-like form and cooking method tempts comparison to a French crepe. Though often used for bread, kisra is also eaten as a fermented porridge or drink. Traditionally made with sorghum, a grain native to Africa, kisra can also be made with whole wheat. Cooking with this thin batter takes some practice, so check out this video for inspiration.

Idli

Traditional foods across the Indian subcontinent consistently use fermentation, even in some desserts! One popular fermented comfort food is the idli, from the Southern part of the continent. Idlis are made from fermented lentil and rice batter. They are traditionally cooked by steaming the fermented batter in special idli molds. When done right, idlis are a wonderfully light and fluffy protein filled snack, often eaten for breakfast.

Injera

Injera is traditional sourdough flatbread eaten in Ethiopia and other East African countries. Injera is made from fermented teff flour. The fermentation process gives this bread its characteristic flavor and sponginess. Injera dough is poured, much like pancake batter, into a large pan where it develops a very porous structure that makes it perfect for soaking up the fragrant, spicy stews and sauces typical of East African cuisine. Think of it as an edible utensil!

Khuley, Bilinis, and Brittany Crepes

Though these delectable examples of fermented buckwheat breads are from diverse places, they are quite similar. Buckwheat is found in many traditional Asian and Eastern European diets. Despite its name, buckwheat is not a wheat at all. One of the three pseudo grains, buckwheat is considered a grain due to its similarity to cereal grains from both a culinary and nutritional perspective. Unlike cereal grains, buckwheat contains all nine essential amino acids making it a complete protein! Khuley from Bhutan, blinis from Eastern Europe and Russia, and Brittany Crepes from France all use a thin buckwheat batter fermented for varying amounts of time to create a wonderful nutty and tangy pancake-like bread. Buckwheat flour means so much to the Brittany heritage in fact, that Breton buckwheat flour has a protected geographic indication status.

The above just scratches the surface of traditional leavened bread. Until the widespread introduction of commercial yeast in 1876, bread was always leavened by natural fermentation using either bacteria colonies from previous fermented bread (this is your sourdough starter) or bacteria from the air. Therefore, most leavened traditional breads that call for yeast today were originally made by natural fermentation. A quick Google search should yield sourdough versions of these traditional loaves if you are looking to experiment! We’d love to hear what fermented breads you’ve been cooking up or are looking forward to trying. Please share with us below! (Abby)

Comments

Add a Comment